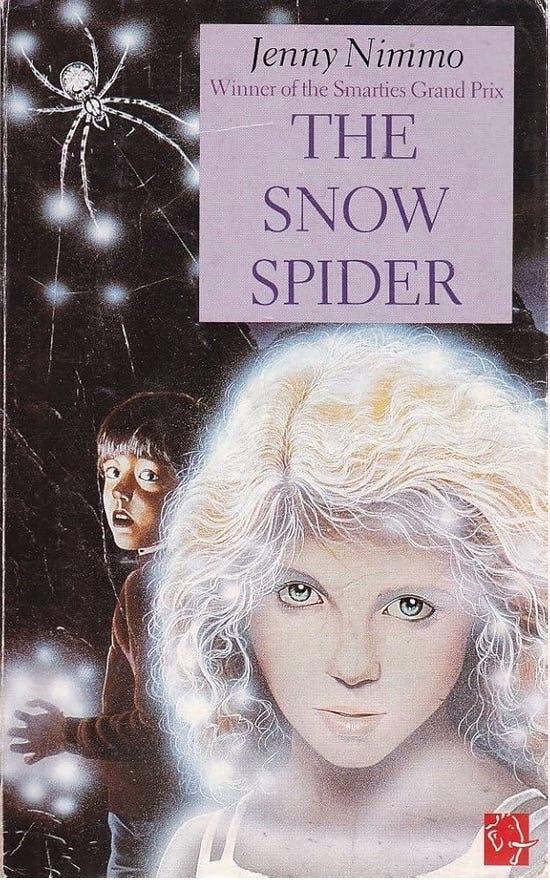

10. Jenny Nimmo and the Snow Spider

I was given Jenny Nimmo’s The Snow Spider for my 9th birthday. There had been a TV adaptation (which I hadn’t seen); even now, I remember the spell that it cast, not least because it beings with the hero, Gwyn Griffiths, also reaching the grand old age of 9.

Reading it, and its sequel Emlyn’s Moon again, this time to a child, I can report that they have lost none of their charm. First published in 1986, The Snow Spider is heavily influenced by Alan Garner and Susan Cooper, and the idea that folklore and myth imprint themselves even on our modern age. Nimmo sets her story in Wales. There is a lot to be said about what is “Celtic” and what isn’t: remember Tolkien writing to Milton Waldman, talking of “the fair elusive beauty that some call Celtic (though it is rarely found in genuine ancient Celtic things.)” In other words, people like Yeats and the bonkers Robert Graves have much more to do with what we understand as “Celtic” than what Celtic really was. But that’s for another essay.

They are ghostly, silvery books, lit by moonlight and full of shadow. What really struck me in both books was the sophistication of the language, allied with a plot and mode of storytelling that can be opaque, relying as much on what isn’t told as what is. Such a method would not be countenanced these days, and I wonder if the children’s literature machine has underestimated what its readers are capable of. The emotional texture of the books is both powerful and subtle, dealing with families breaking up and coming together, and with a richness of vocabulary that might have today’s editors reaching for their pens.

The plot comes straight from fairytale - Gwyn Griffiths’ sister, Bethan, has vanished. This is a version of the Childe Roland story, where Roland and his sister Burd Ellen are playing ball near a church; Ellen goes to fetch the ball and walks round the church widdershins, and is snatched away by the King of Elfland. (It is a story I used myself in The Broken King, and Ross Montgomery recently put it to good use in Chime Seekers). Gwyn has a dotty old grandmother, Nain, who tells him that he is a descendent of several powerful wizards, and gives him some objects, telling him to throw them to the wind. The only one that he musn’t use is a strange wooden horse.

The first thing Gwyn gives to the wind is a brooch, and it brings back with it the snow spider, which he calls Arianwen. Later that night, the spider weaves a silver web, in which he sees his sister in ghostly, silvery form, and, at other times, another world inhabited only by children. It’s exceptionally creepy. This place is devoid of colour, and the children possess great knowledge, and seem to move as one organism.

Why a spider? I wondered as a child. And why a web? It puzzled me then; decades later, I wonder if Jenny Nimmo knew of Lucian’s A True Story, in which spiders spin interplanetary webs. I think there is also something of Arachne here, and the dangers of playing with powers beyond human ken. Could there, too, be a hint of Ariadne in Arianwen’s name, and a silken thread that leads to the truth?

Creepier still is when Bethan returns, in the form of a pale girl called Eirlys, and tells Gwyn that she is happy, living on a planet where the inhabitants stay in the form of children for ever. It is a kind of Fairyland, but eerie and sterile. Doppelgangers and reflections remain a powerful thread in the novels: in the sequel, the heroine sees what she thinks is herself in the mirror of the web, but turns out not to be.

Gwyn, of course, grappling with his new-found powers, in the end releases the wooden horse into the wind, and it brings back a demon from the past. This leads to one of the most powerful scenes in the book: but it’s not told from the perspective of Gwyn; we only learn about it when his friend is rescued from the mountains. Gwyn’s magic, over a gruelling night, contains the trickster, and the world returns to safety.

As a child, I desperately wanted Bethan to come back to Gwyn and her family: but as an adult I realise now both that Fairyland functions as kind of analogue to the world of the dead, and also that were she to come back, she would be so altered that she would hardly be herself any more. Gwyn’s family come to terms with her disappearance; and Gwyn learns to control his powers: as we must all adjust ourselves to loss, and learn to control ourselves.

The sequel, Emlyn’s Moon, is even more oblique. I made the mistake of ordering an American second hand copy online, which changed Mam to Mom and all the rest of it; so that was swiftly rectified and I found an old Mammoth copy. The heroine here is young Nia, and Gwyn only has a cameo (though significant) part. The role of spider and Arachne is transferred to Nia, with a sub-plot concerning her burgeoning artistic abilities: she is making a tapestry, or patchwork, for a school project. She herself is a storyteller, weaving what she sees into her work, and the parallels between art and magic are clear.

The making of art is a motif: Idris is a local bohemian artist, and his son Emlyn tells Nia that his mother has gone to the moon. The narrative unfolds slowly, but that did not affect the enjoyment of it: there were still cries of “more” when I came to the end of a chapter. The main plot concerns Emlyn, on whom the strange silver children have fixed as a potential recruit; the secondary plot revolves around the location of Emlyn’s mother, who lives in a house surrounded by strange, cold, white flowers. She has fled Idris, and is being helped by Gwyn’s father: family rivalries boil under the surface of the book.

It seems extraordinary that there is hardly any magic at all. And yet the narrative moves with great tension. Gwyn, who is Emlyn’s cousin, at one point comes close to using magic to fight him, but controls himself; it’s only at the end, when Emlyn comes under attack from the creatures, that he calls on all his powers to create an illusion and scare them away. Once more, families who have sufferred are brought together.

What’s also interesting is that we are never told anything explicitly. Who the children are, and what they want, is never explained. We are not told who the heroes of old are that Gwyn calls upon for his illusion. The silver children remain a terrifying force, nevertheless, perhaps because of their apparently motiveless interest in our planet. But art and magic can defeat them.

In these books, mingling fantasy and science fiction, Nimmo creates her own distinctive and sophisticated brew. The final part of the trilogy is The Chestnut Soldier: I, and the small ones, can’t wait to read it.