We are soon to be treated to a new book about Richard Burbage, one of William Shakespeare’s greatest actors, Richard Burbage and the Shakespearean Stage, by Siobhan Keenan.

Looking at the Burbage family helps to set William Shakespeare into context, and I think is a very useful exercise for anyone interested in the period. He was closely linked to the family, in many ways. They were from similar, middle-class stock: the Burbages very likely came from Kent, and James Burbage (born c. 1531) married the daughter of a tailor. Their lives highlight the importance of craft: of the interlinked trades and connections that powered the Elizabethan theatrical world.

James Burbage was a joiner / carpenter, and a member of the Earl of Leicester’s players, being one of its lead players. He visited Stratford upon Avon in 1573 and 1577 - when Will would have been exactly of an age to be mightily impressed by visiting troupes of actors. (How excited must that small boy have been at the prospect of Leicester’s men returning, perhaps putting on again a play that he loved.) It is entirely possible that Will saw James Burbage acting, and, given his own father’s prominence in the town, and involvement in the arrangements for the troupe, may even have met him. This could well have been the link that later brought Will to London.

James Burbage’s contribution to the London theatre world is paramount. It is hard to believe now, but there were no permanent theatres at the time, and actors toured around the country. You can imagine how exhausting it must have been; and James saw the benefit of a permanent place for putting on plays.

Thus “The Theatre” was born, in Shoreditch, at the edge of the city, a liminal place where a new society was forming. James was fully involved in it, day to day: his house stood nearby. (As Will is so closely linked to the Globe and the South side of the river, few remember that this place was where he learned his craft: John Aubrey says he first lodged in Shoreditch.) The Theatre’s audience was mixed: courtiers, tradesmen and students all thronged its precincts. It was clearly a meeting place for gossip and entertainment, as people would arrive an hour or so before the play began, to mingle and read.

There were other connections: in 1584, Henry Carey, Lord Hunsdon became James Burbage’s patron - this is significant, because Hunsdon was also the patron of James’ son, Richard’s players, which included a certain William Shakespeare. And when Hunsdon died, his own son, George, took on the patronage.

Theatre was in the Burbages’ blood. They were probably the first theatrical dynasty. James’ two sons, Cuthbert and Richard, became prominent in the field, as investors, actors and playwrights.

Richard is the more famous, and was only 8 when The Theatre opened. He would have grown up deeply immersed in plays and acting. There is a parallel here too, between the young play-struck Will, and Richard, who learnt his craft at his father’s knees. (I note here that John Webster’s father, a carriage-maker, also had connections with masque and performance, as carriages were used in processions.) The carpentry, the painting, the scene-making: all of these are closely connected, and it’s not hard to see how both Will and Richard fitted into this world. (They would later appear on stage together, but no doubt they did here too).

Owing to various problems, The Theatre had to be physically dismantled - the Burbages’ carpentry experience coming into play again - and brought bodily to the south of the river, where the beams and remnants became The Globe: a nice transmutation, reflecting the transformations that happened nightly on the theatre’s boards.

The creative dynamic between Richard and Will led to some of the latter’s greatest tragedies, with Richard taking the lead in Othello, Hamlet, King Lear and Richard III, among countless others, which, alas, we will never know, as records have not always survived. One thing we do know, however, is that John Lowin was almost certainly the “second man” to Burbage, playing, eg, Iago to his Othello. I’ll come to this again at the end of the post.

Will wrote the parts for Richard, knowing his talents, and pushing him to achieve the highest range possible. It must have been thrilling to work with such talents, so closely; it’s hard to think of a similar actor/writer relationship these days. Whilst many seek biographical elements in Hamlet from Will’s life, it’s curious to note that Richard’s famous father, John, had died before the play was put on: and it would have been Richard speaking Hamlet’s lines, after all.

Richard Burbage and William Shakespeare were a powerful force in the theatre world. Their friendship gave rise to an anecdote, recorded by John Manningham in his diary: Richard had been arranging a tryst with a female fan, and Will overheard their amorous chatterings. Much to Richard’s detriment: for when Richard later went to the arranged place, Will was already there, and sent a message back: “William the Conqueror was before Richard III.”

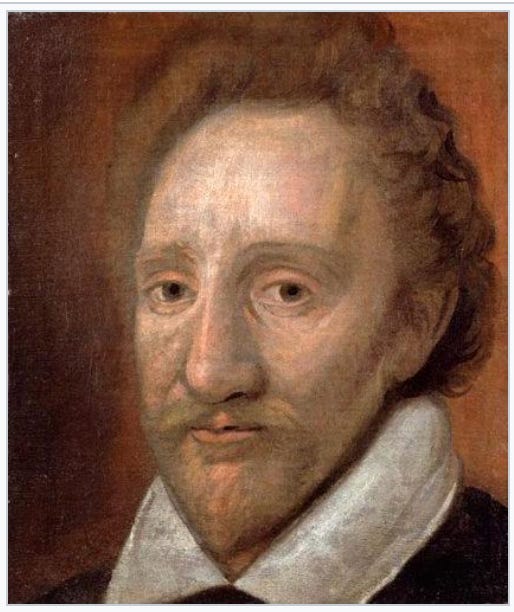

A seventeenth century witness, Richard Flecknoe, described Richard Burbage as: “a delightful Proteus, so wholly transforming himself into his Part, and putting off himself with his Cloathes, as he never (not so much as in the Tyring-house) assum'd himself again until the Play was ended.” Richard was also a talented painter (some think the picture above is a self-portrait), and his closeness to Will is also demonstrated by the fact that both were asked to create an impresa (a coat of arms and a motto) for the Earl of Rutland, with Richard providing the painting, and Will the motto. The playwright also left money to Richard in his will.

When Richard died in 1619, three years after Will, the mourning in London was so great that it eclipsed that for the Queen, who had died the same year. This, argues Chris Laoutaris in his Shakespeare’s Book: The Intertwined Lives Behind the First Folio, was part of the impetus for the collection of the plays that were to become the Folio, as it brought renewed interest in the works that Richard had given life to: among them, remembered for playing “Young Hamlett”.

Richard’s brother, Cuthbert Burbage, outlived him, becoming a rich man, and buying a country house in Kent: he married the daughter of a gentleman, and his daughter, Elizabeth, married into the gentry, just as Will Shakespeare’s grand-daughter Elizabeth Hall did. The Burbages’ ascent describes exactly the kind of upward social movement that the Elizabethan world afforded to those who were talented and ready to take it. They were linked in myriad ways to the aristocracy, and to other families in the busy world of the theatre: much like William Shakespeare and his own family.

So what of John Lowin? His life contains enough material for another post; suffice it to say for this one that he lived longer than his fellows, dying in the 1660s, and signed the dedication of the Beaumont and Fletcher Folio in 1647, which says: “"But directed by the example of some, who once steered in our qualitie [i.e., John Heminge and Henry Condell], and so fortunately aspired to choose your Honour, joyned with your (now glorified) Brother, Patrons to the flowing compositions of the then expired Sweet Swan of Avon, SHAKESPEARE....”

Lowin was in the King’s Men with Burbage; he acted alongside Burbage, and worked (and acted, no doubt) alongside William Shakespeare. He would have been there when the plays were written, and like Burbage, would have memorised his lines pretty much the day or the day before the play was put on. His signature demonstrates a direct link to both Burbage and Shakespeare: more people should know of it.

Philip Womack’s most recent novel is Ghostlord.

Very much enjoyed this piece - you might be interested to know that I wrote a short book - Master Will and the Spanish Spy - about Shakespeare’s first encounter with the Burbages in Stratford when he was young… published by Barrington Stoke in 2016, and now sadly o/p… I would also recommend Daniel Swift’s excellent book on Burbage, The Theatre etc, The Dream Factory, published earlier this year…