Thomas Kyd wasn’t even considered the author of The Spanish Tragedy until the late 18th century, when Thomas Hawkins picked up on a reference by Thomas Heywood to ‘M. Kid, in The Spanish Tragedy’.

It seems extraordinary, really, given that it was one of the most popular plays of the Elizabethan stage (though it is rarely performed today, and, I imagine, still less read); yet, since plays were the property of the acting companies, and if we remember that Shakespeare’s name wasn’t on his printed plays until he began to be famous, it becomes less so.

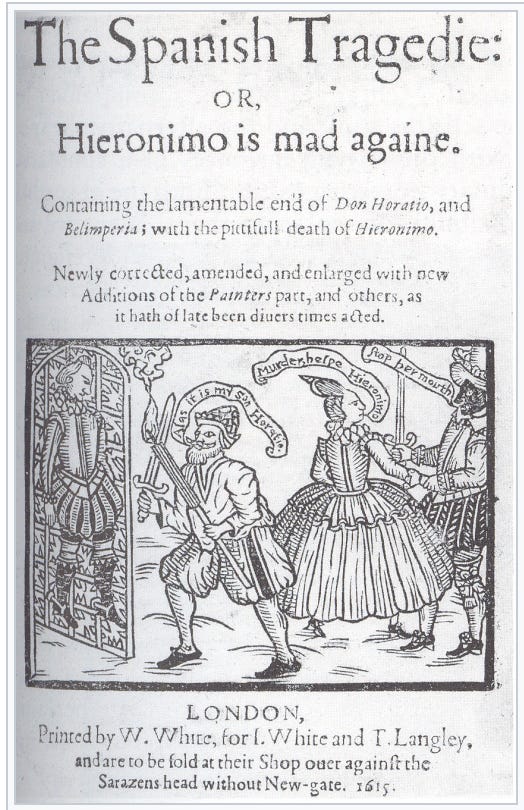

I decided to re-read The Spanish Tragedy: or, Hieronimo is Mad Againe, because I wanted to contextualise the plays of William Shakespeare. Kyd was the son of a scrivener, from a similar middle-class background to Will. Some think that he continued his father’s trade, and indeed, we have specimens of his hand-writing which are rather beautifully done.

Kyd is also notable for having shared a room with Christopher Marlowe. When some incriminating papers (which may have been planted) were found in his room, Kyd was imprisoned; after Marlowe’s death, Kyd claimed that the papers were Marlowe’s. He was released, but died shortly afterwards, presumably partly from the privations he’d endured. A tragic ending, and a talent cut short.

The Spanish Tragedy was an absolute hit of the Elizabethan stage. There were twenty-nine performances between 1592 and 1597, and at least eleven editions between 1592 and 1633, beating any Shakespeare play. Pepys saw it, nearly a hundred years later, noting it in his diary (though he didn’t enjoy it.)

And reading it, you can see why the Elizabethans went for it. It’s a revenge story, and it may (if its earliest date, 1587, is correct) indeed be the very first revenge play of the period. It’s about sex and love, violence and horror, and the shadows and corruption that lie under the surface. There are ambiguous father / son relationships; the dialogue is frequently swift and laden with double meaning; the stage action is haunted by mirror images and doubles. Ironies proliferate, too, and as Hieronimo’s revenge is delayed, we are yet hurtled onwards into a Senecan blood bath.

The plot is as follows. Andrea, a Spaniard, was in love with Bel-Imperia, a Spanish princess. Killed by Balthazar, the Portuguese prince, in battle, the play begins with Andrea’s ghost watching events unfurling below. The personified Revenge stands by him: it must have been a frightening sight on stage. The audience watches Andrea, who is watching the play as if it were real: already there are complexities of narrative distance.

The play’s main plot concerns Bel-Imperia, who wants her revenge on Balthazar. Her father (the Duke of Castile) and the King of Spain, however, want her to marry him. She decides that she will love Horatio, the son of Hieronimo, the Spanish Knight-Marshall, who captured Balthazar in battle, and will thus further her revenge. A further rivalry exists between Horatio and Bel-Imperia’s brother, Lorenzo, who both claim to have captured Balthazar. (Horatio has the stronger claim.)

When Horatio and Bel-Imperia meet and declare their love in an arbour, they are surprised by Balthazar and Lorenzo, and Horatio is hung up and stabbed. Excessive, you might think, but it’s only the start. Hieronimo is woken from a dream and discovers his son’s body; he then slowly goes mad, before he takes his revenge in inventive and exciting form. He writes and puts on a play within a play, Soliman and Perseda, in which Lorenzo, Balthazar and Bel-Imperia are the actors: only, when the actors are killed, it is real knives that are used. Hieronimo then reveals his son’s dead body: you can well imagine the gasps from the groundlings.

Kyd shows mastery of craft, here, as at the start of the play, Hieronimo puts on a masque for the King of Spain: he is a director and entertainer already. In the masque, three knights defeat three kings, and hang up their scutcheons. The gallows, and the hanging up of the shields, and the arbour where Horatio is hanged, all function as weird echoes of each other: to be raised is to be triumphant as well as to be killed.

The play finishes with Hieronimo, prevented from hanging himself in a cruel doubling of his son’s death, biting out his own tongue, and then killing both himself and the Duke of Castile with a knife that he’s given to sharpen his pen. The author of the play kills with a play: right at the beginning of our modern theatrical tradition, we have a drama that is fully aware of the power of theatre and of its meta-theatrical possibilities. It’s dazzling. The play ends with Andrea and Revenge gloating, and promising endless torture for the wrong-doers.

As an agent of revenge, Hieronimo is tormented by grief for his son, and yet there’s also something unusually excessive about his grief. The father / son relationships are deeply strange: the King of Portugal seems to want to believe that his son, Balthazar, is dead; meanwhile, Hieronimo, when he meets an old man (whose son has also been killed), mistakes, in his madness, the old man for his son. The Elizabethans were absolutely fully aware of the terrible cycle of revenge, and Hieronimo in his brutal vengeance becomes a Fury himself. Classical references to Hades and the dark gods of the underworld abound: this is not a play with much tonal light and shade.

Kyd may have been the author of what’s called the “ur-Hamlet”, a play referred to by Thomas Nashe, and which is most likely a source for William Shakespeare’s Hamlet. There are plenty of resonances between The Spanish Tragedy and Shakespeare’s Hamlet: there is the madness of the revenger; the ghost; the madness and suicide of Isabella, in which we see a foreshadowing of Ophelia; the play within a play, which is put to use by Hamlet with the Mousetrap; and the delay of Hieronimo and Bel-Imperia’s revenge.

But where Shakespeare’s Hamlet is a philosopher, Hieronimo is not; although he soliloquises about his plans, he never reaches the same heights of thought. It’s likely that the “ur-Hamlet”, if it had survived, would have been similar: more straightforward, moving much more quickly, and with more Senecan influences than Shakespeare’s version.

Understanding this play helps throw light on the tastes of Elizabethan audiences: and it also shows where Shakespeare stood out from his contemporaries, and what makes his Hamlet such an extraordinary, luminous and intelligent piece of work.

Nevertheless, The Spanish Tragedy is absolutely worth reading: I promise, you’ll be hooked.

IN OTHER NEWS

I’ve written pieces for The Spectator about rising illiteracy and being in Pseud’s Corner. I’ve also reviewed five children’s books for my regular round up in Literary Review.