The Arrow of Apollo, and the fall of Unbound

Nearly ten years ago, now, I had an idea for a novel. Whilst a lot has been written about the major heroes of Greek and Roman myth, very little - if anything - has been about their children. Because the heroes did have children, and those children had children, and so on, until they became the Greek tribes themselves, and who knows, you or I may be descended from Hercules.

Aeneas’ son, Iulus, founded Alba Longa, and became the ancestor of the Julian family. (We all know, naturally, that his other son Brutus came to Britain.) Orestes married, and had children, including Tisamenos. What, I wondered, would happen if these children were thrown into mythical adventures, having to escape their past, yet face the future?

And so The Arrow of Apollo was born. The premise was that the gods were growing bored of the earth, and leaving, thus paving the way for the return of older, chthonic beings. Few remember that Apollo snatched his oracle from Python: so what, I wondered, would happen if Python wished to reclaim what had once been his own?

It was easy to place within the market: Rick Riordan’s Percy Jackson series was riding high, and The Arrow of Apollo was the ideal next stop for readers, a stepping stone between Percy Jackson and Roger Lancelyn Green.

I’d just published a book, The Double Axe, which reimagined the story of the Minotaur, and so it seemed a good fit. For various reasons, however - not least that publishers seem wary of anything that doesn’t retell a myth directly - and, in fact, largely due to happenstance, I took the manuscript to the crowd-funding publisher, Unbound.

The idea was deceptively simple, and reassuringly old-fashioned. In the 18th century, readers would subscribe to a novel before it was published, thus ensuring sales. This was, in essence, the same idea: authors would raise the money for the book.

The Unbound list had a strong scattering of household names and writers who wanted to publish books that traditional publishers didn’t necessarily want, (including some I knew personally): it seemed very attractive. Unbound would produce a hardback for my subscribers, and simultaneously put a paperback out onto the market.

It happened quickly. I attended a meeting at the Unbound office, with a few other authors, of which I remember little, other than that I found the whole funding process rather bewildering.

And then began the graft.

At the time, I was teaching, almost full time, at two universities, alongside other teaching commitments. I had a very young child; we were moving house; I was also trying to write a new book, and attend to all the other vagaries of freelance life. Yet now, for about half an hour every morning, I hunched at my computer, sending out emails asking people to put money towards a children’s novel they hadn’t read yet.

In a sense, I was lucky: I have a wide network of family, friends and acquaintances, of amenable-minded colleagues, of people who’d read my earlier books and were interested to see what might happen next.

But I would never repeat the experience. There is something a little humiliating about sending out such messages (even if I know that people don’t particularly mind receiving them: the worst they can do is press delete).

I can’t, precisely, remember how long funding it took now - I think I’ve blotted most of it out of my memory - but I think it was fully funded within a few months. There were moments, of course, when I dreaded moving further and further down my list: teachers from my school? someone I met at a party once, ten years ago? people who knew your parents? The net was cast wider and wider. And I will admit that I was largely astonished by generosity: some were very generous indeed - sometimes, in fact, from unexpected quarters.

The sum I had to raise was large - over £10,000, as I recall, possibly even as much as £12,000 - and as we neared the target, I began to feel excited about the project. This was a commercially minded book, with a potentially large readership: children who love Greek myths; adults who enjoy them; teachers, librarians, and so forth. In 2020, I was also publishing another book, for adults, with Oneworld, How to Teach Classics to Your Dog. The two books, though with different publishers, couldn’t have aligned more perfectly.

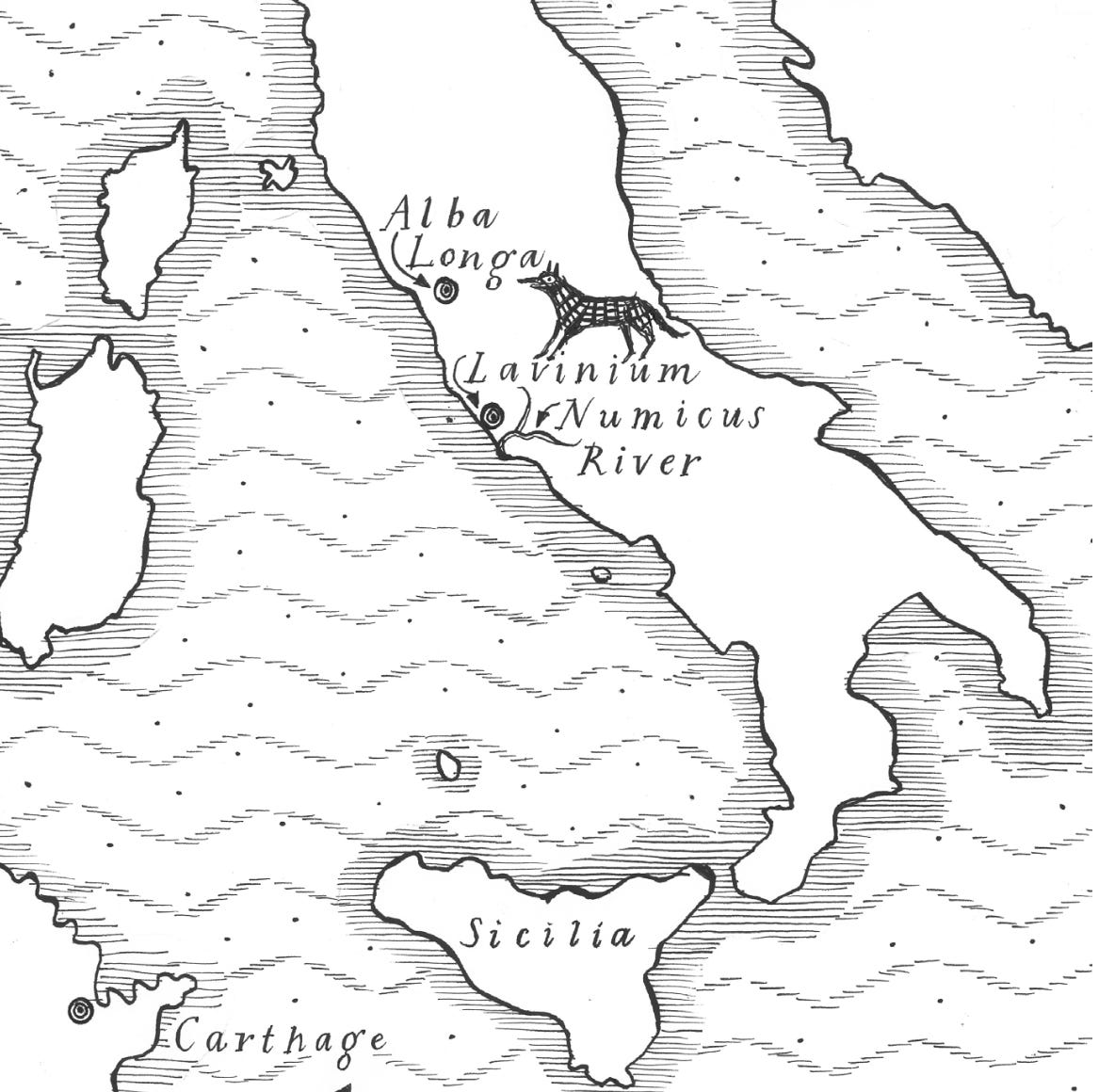

Unbound hired a freelance editor, Elizabeth Garner, who was wonderful. A novelist herself, she had an instinctive feel for narrative, and made some very thoughtful suggestions which helped improve the book’s overall arc. Illustrations were provided by Emily Faccini, who created a lovely map that I still have on my noticeboard. The cover design (see above) was both striking and the sort of thing that sells books. The hardbacks Unbound made were gorgeous, proper, solid things that still make me happy when I pick one up, and the paperbacks were professionally produced. They’d also signed a deal with an audio producer for an audiobook.

All authors think that the next book is going to be “the one”: and at this point, I genuinely believed that The Arrow of Apollo would be.

The first sign of unease came when I sent a message to the Unbound team, asking what their marketing and publicity plan was. The answer came back: they didn’t have a marketing department. I began to worry, a little - how would the paperback reach bookshops? And, even though I have a few contacts in the media world, how would people find out about the book?

The Arrow of Apollo was scheduled for launch in May 2020. I don’t have to tell you what happened next, but when I suggested delaying publication until things were more settled, I was refused, and the book was published in a week when no bookshops were open, and no schools either. I had been supposed to sign the hardback copies for my subscribers; instead, I signed stickers, which were stuck into the books in the warehouse. The audiobook arrived: it sounds, to me, as if it was read by a robot.

I held a slightly hysterical online book launch (at which one of my friends’ names appeared on Zoom as Cock Munch, much to my relatives’ amusement). I didn’t know what to do at it; nobody really did. It felt anti-climactic. Later, I asked my friend Cat Ward to interview me , which she gamely did (look at my lockdown hair!). And that, really, was that.

On my own, I managed to get a few reviews placed, mostly in small Classically friendly or children’s specialist magazines. Julia Gray’s review in Literary Review was gorgeous, and I hope you don’t mind me quoting from it here:

“"The Arrow of Apollo ... drawing deeply and with great intelligence on classical mythology, is beguilingly original. ... The prose is both elegant and muscular ... There is much to admire in this intriguing, ambitious, immersive book."

The big papers, however, largely ignored it. I was disappointed, to say the least.

Then, eventually, school visits began again, and The Arrow began to gain some momentum. Children always enjoyed it; adults too. It built up good reviews on Amazon. Parents would sometimes stop me to say how much their child (or they themselves) had enjoyed it. It worked very well alongside The Double Axe, and sometimes Classics departments would ask me to give talks to schools. Numbers remained steady: it was becoming what I had hoped, a solid backlist title that remained on the shelves and gradually grew a readership. (And all this without any help, in promotional terms, from Unbound itself.) Earlier this year, in March, The Arrow of Apollo was reprinted, with extra praise on the front. Things, I thought, were looking up.

Unknown to me, things were happening at Unbound. I’d already noticed that my editors changed frequently, without my being informed: I’d email someone, only to find an out of office reply, and a re-direction to someone else. Odd, I thought, not to tell the authors. The distributor changed, also without my being notified: when I tried to make an order of books for a school visit, I was told that a different organisation was being used, and I’d have to set up a different account. Again, odd. Little did I know that this was all indicative of an office in crisis.

And then came the big announcement. Unbound was in trouble. They didn’t tell us why - when I later discovered that they’d sunk vast amounts of money into an AI tool, I nearly fell off my chair. (Who needs an AI tool to tell you how much something might sell?) Unbound were partnering with another publisher, Neem Tree Press. I looked them up, and they seemed like a Good Thing, with a strong YA list that The Arrow sat nicely alongside. Unbound, they said, would honour all royalty payments due to authors.

Rumblings began. I’m not sure of the exact process, but Unbound became Boundless, and announced that they didn’t have the cash to honour payments. Online, I saw other authors, whose books hadn’t yet been published, in despair. I saw those owed thousands of pounds. And I began to wonder what was happening to my book. It had just been reprinted: where was the money from sales going? What’s happening to the money from the audiobook? I emailed the Boundless team once, twice, in the end, half a dozen times and more, asking simple questions: what are you doing with my book? And nobody ever answered.

I still don’t know, now, if I’ll ever get the money from the sales of those books. Given the precarious existence of most authors, this is disappointing beyond belief. I know exactly how many have sold; I know how many are in the warehouse. Yet the likelihood of seeing even a farthing from all this is vanishingly small. When I think of all the time spent writing the book, funding the book, working on what publicity I could during a world-wide pandemic, going round schools, and so on and so on: well.

When I asked for my rights back, earlier this week, things happened very quickly indeed, and within a day I had them back. The remaining books in the warehouse are, currently, mine.

I’m going to transfer my rights to another publisher, and The Arrow of Apollo will continue to exist, and, I hope, continue to find its readers in the way that I’d always wanted. So here’s to its new, phoenix-like beginning.

If you’ve read this far, and would like a copy, the best thing to do is to ask me directly: I have a few left over from a school visit.

With luck the rights transfer should happen pretty quickly, and I’ll be earning money from it once more in the autumn.

Sorry you've been caught up in this too. Nightmare.

(That is indeed an excellent idea for a book though... I hope it lives on.)

How frustrating Phil - I’m so sorry. Please take the opportunity to write a sequel. Kit (now 7 and also a keen consumer of Percy Jackson. I deliberately don’t call it reading as I swear he eats them) is very keen on AofA and would love it if there were more